Recession or Not, Here We Come

Are we heading into a recession or not?

The U.S. economy grew at a 2.0% annual rate in the 2nd quarter - a long way from a contraction. Fed Chairman Jay Powell just said the central bank does not expect “at all” that a recession is approaching.

But prediction markets are a bit more equivocal, putting the odds of a recession during President Trump’s first term around 40 percent. And then there is the famed “yield curve inversion” – the confluence of bond market movements that convinced many that a recession was approaching in the next couple years.

The truth is we just don’t know. Forecasting recessions is one of the least precise tasks we perform in economics, nestled right behind predicting short-term stock market moves. If we’re honest, the best we can do is point to encouraging or worrisome indicators and take our best guess about how they balance each other. That said, here’s what the landscape looks like and what it could mean..

Defining a Recession

Before getting into all that, what do we mean by a recession? We don’t even have complete agreement on that. In popular parlance, a recession is two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth. In the United States, however, the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) marks the start and end of business cycles (recessions and periods of growth). It provides a different definition:

“a recession is a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales.”

So, a widespread and persistent downturn that we generally associate with a sense of malaise. Per the NBER, the last recession – one of our worst – started in December 2007 and ended in June 2009. That means the ensuing expansion has lasted more than ten years – longer than the longest stretch we’ve had in the United States (which was March 1991 to March 2001).

This leads to another question: what brings on a recession? This is the subject of hot debate. One view is that there are business cycles that operate with some predictability. To illustrate such a story: Consumers run up excessive debt and need to pull back on their spending; lower consumer spending means businesses invest and hire less; consumers cut their spending further when they lose jobs. Then, at some point, old cars and appliances need replacing and people with kids move from cramped apartments to starter homes; consumers go out and buy; businesses hire and invest to meet those consumer demands; wages rise and jobs proliferate. Thus, the cycle goes down and up.

A different view holds, in the words of former Fed Chair Janet Yellen, that expansions don’t die of old age. In this view, an expansion can keep going indefinitely, if managed properly. Recessions happen when those managing the economy make policy mistakes. That might be interest rates that are too high and choke off economic growth. Or it could be misguided fiscal, regulatory, or trade policy.

Forecasting a Recession

Given this fundamental disagreement about what causes recessions, it’s not hard to see the difficulty in forecasting when the next one will arrive. Even so, there are some indicators that have traditionally done very well at presaging downturns. Perhaps foremost among these is the “inverted yield curve.” The curve in question traces out the interest rates the U.S. Treasury needs to pay to borrow money. In general, if an investor sees good economic times and growth ahead, that investor will want to be compensated for having his or her money tied up in a Treasury bond. The longer the money is tied up, the higher rate they will demand.

Thus, one expects that a 10-year bond will have a higher interest rate than a 2-year bond. And that’s true most of the time.

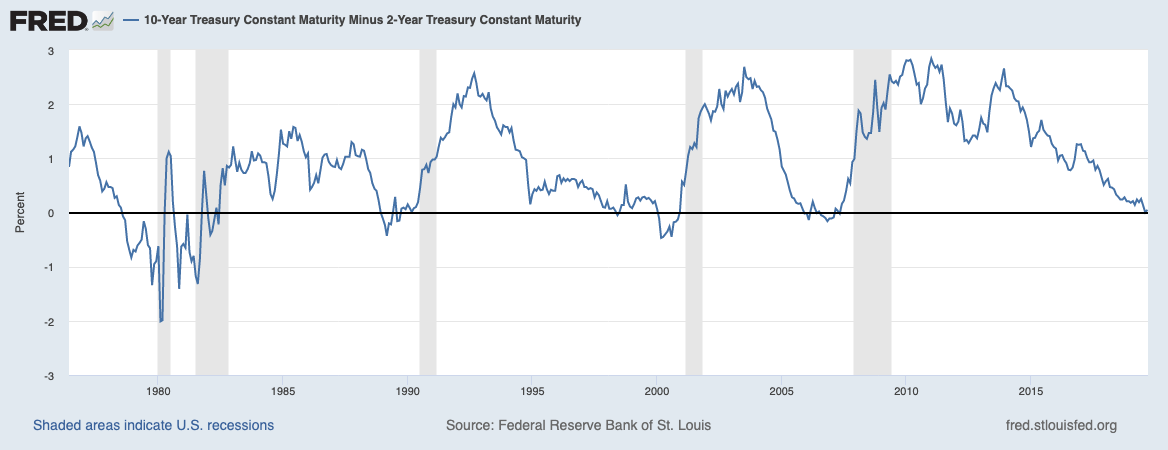

Every now and then, however, the interest rate on a 10-year Treasury dips below that of a 2-year. That is the condition people refer to as an “inverted yield curve”. In the chart, that occurs when the line dips below zero. The remarkable thing in the chart, which traces U.S. experience back to 1976, is that the curve inverts before those vertical gray bars, and only before those vertical gray bars. And those vertical gray bars are recessions.

Why would this be? For the yield on a 10-year bond to be lower than that on a 2-year, the investor has to anticipate dropping returns on investment. That’s the kind of thing one expects to see when a downturn looms. So there’s a plausible explanation for why the indicator should work so well. And we’re talking about this now because the yield curve just inverted at the end of last month.

This is not the only way to forecast a recession, of course. Another popular approach is to look at the various components of GDP, such as business investment, trade, and consumer spending, and see how each component is trending. In recent numbers, stronger consumer spending was more than offsetting weaker trends in business investment and trade. Prognosticators grew more worried in August, therefore, when consumer sentiment weakened late in the summer.

No One Can Say For Certain, But...

Finally, one can ask just how daunting a task it will be for policymakers to stabilize the economy. Ideally, those policymakers would like to enter a perilous period with high central bank interest rates (lots of room to cut), low federal deficits or a surplus (room to spend), a booming global economy (more demand for U.S. exports), and a calming, pro-growth trade policy.

That is the opposite of what we have now in every dimension. Interest rates are low, deficits are high, other major economies are slowing or slumping, and there are estimates that trade policy uncertainty is cutting into U.S. growth.

There is no way to say for sure whether a recession is fast approaching. But there are ample reasons for concern.

About the Author